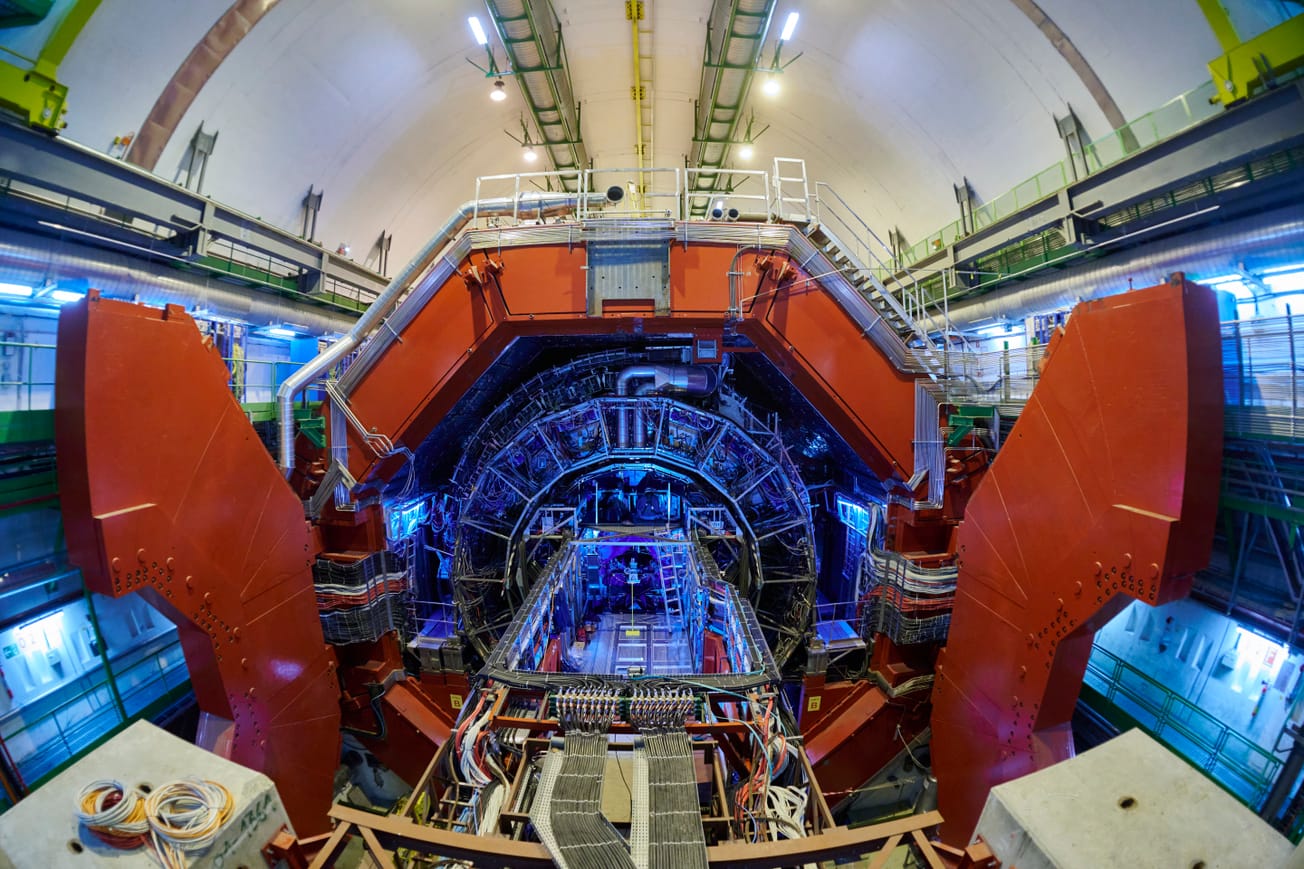

GENEVA (AN) — Researchers at the world’s biggest atom smasher announced they have observed a subatomic particle that physicists have never seen before and could lead to better understanding of a fundamental building block of all matter.

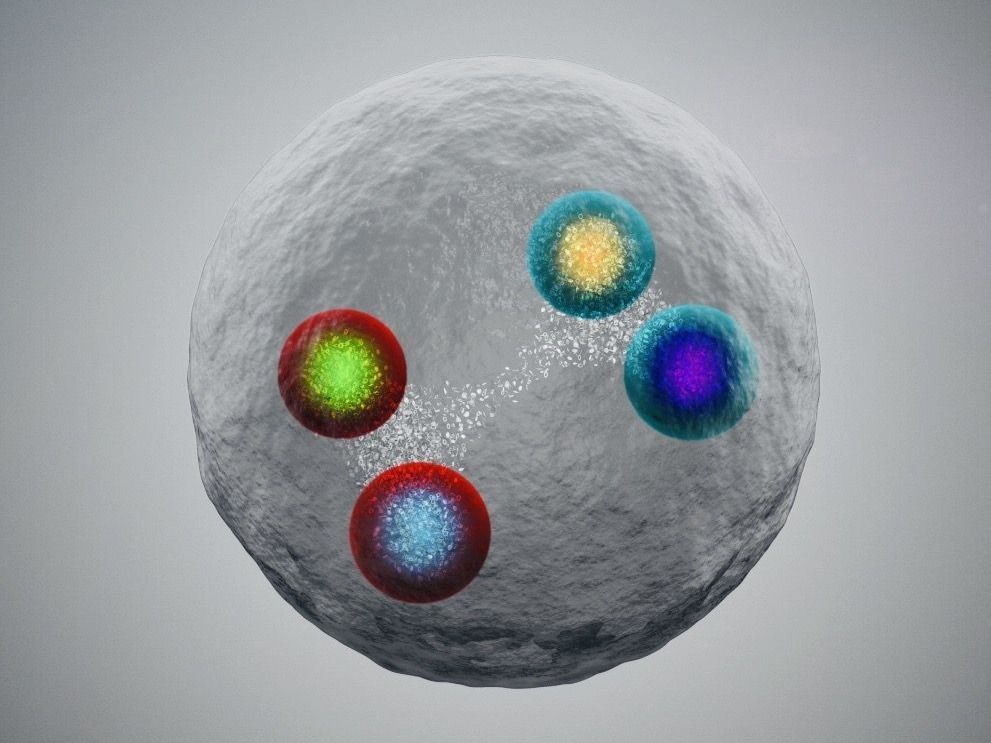

The European Organization for Nuclear Research, known by its French acronym CERN, said on Wednesday this marks the first time that an exotic particle made up of four charm quarks has been seen. The findings, published online on the arXiv preprint server, come from CERN's LHCb collaboration.