Why the push to mine the deepest depths of the oceans? You’re looking at it right now. Maybe holding it in your hand. Perhaps it powered the car that carried you to the office today or it’s helping cool you during a heatwave.

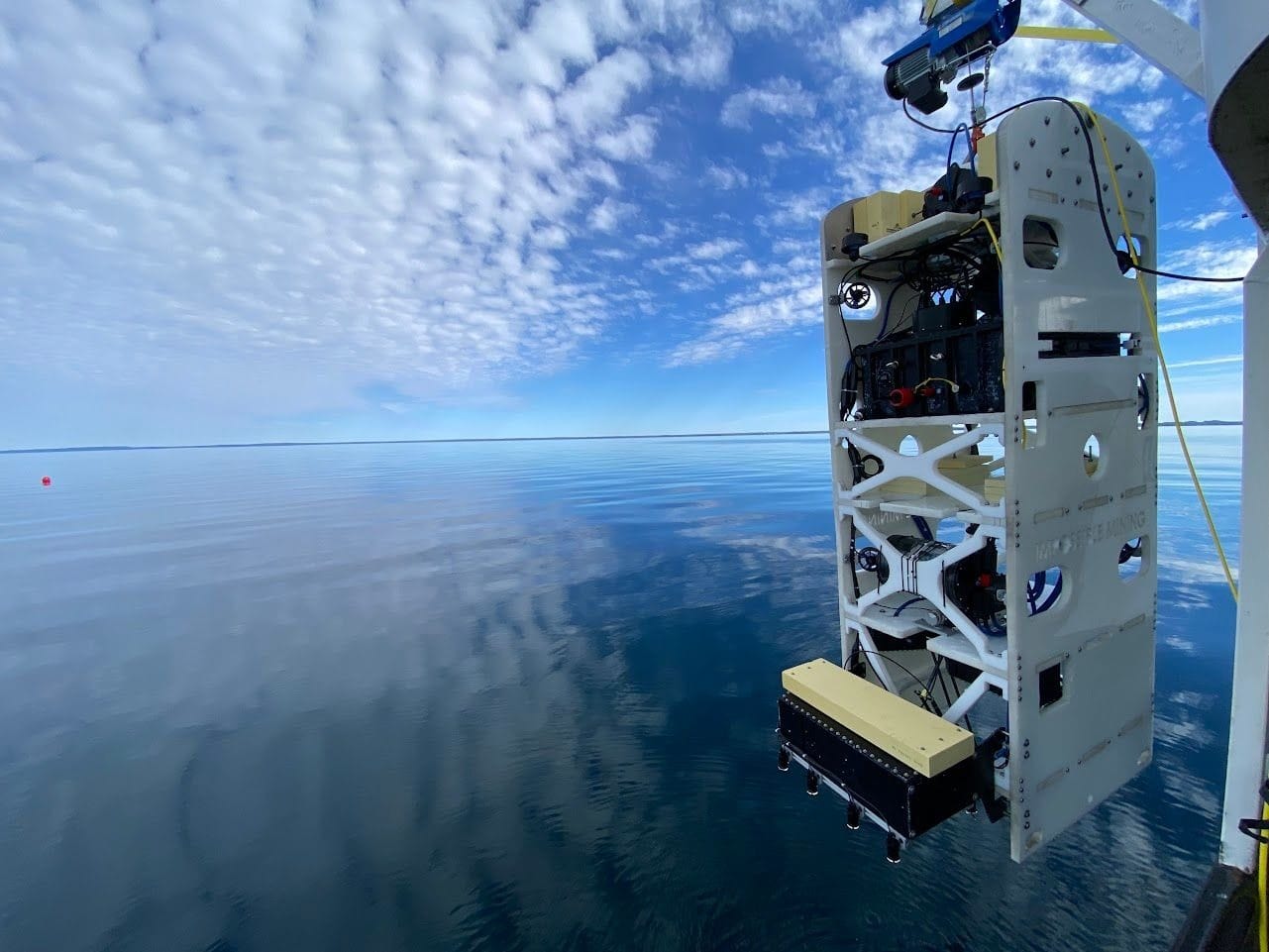

Driven by everyday technology — like our cellphones, computers and tablets — and the batteries to fuel electric vehicles and the raw material to wean the world from fossil fuels, demand for rare and exotic metals is surging. If some governments, financiers and mining conglomerates have their way, the rush to riches could be miles below the surface of the seas.