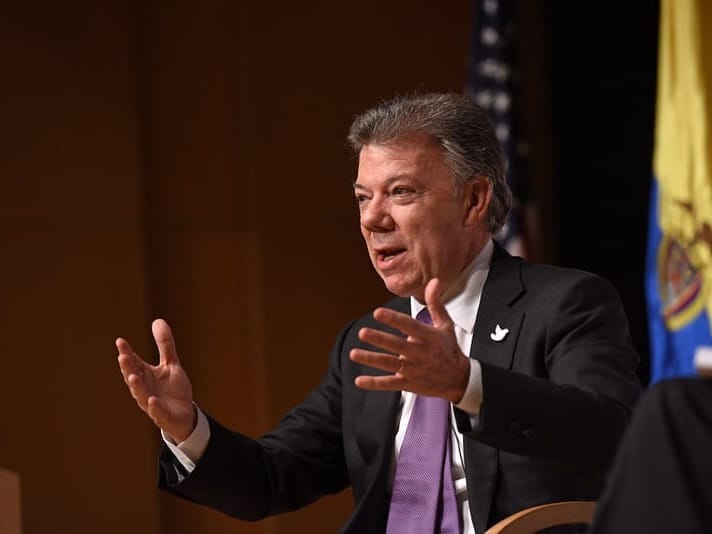

In this interview with International Peace Institute Global Observatory's Albert Trithart, Colombia's former president Juan Manuel Santos answers questions about the future of multilateral cooperation, the importance of private diplomacy, and lessons from the Colombian peace process.

Santos, a former president of Colombia and recipient of the 2016 Nobel Peace Prize, now serves as chair of The Elders, a London-based organization of independent global leaders founded by Nelson Mandela in 2007 to work toward peace, justice, human rights, and a sustainable planet.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: You recently spoke when the latest time change to the Doomsday Clock was announced, bringing the world closer to midnight than it’s ever been. You said "the only effective response is for nations to work together," but it seems more and more that nations are moving in the opposite direction, with the United States pulling out of the Paris Agreement, World Health Organization, and other multilateral institutions. It’s easy to feel hopeless, or at least deeply pessimistic, about the future of multilateralism. Are there any people or places in the multilateral space you’re looking to now for hope?

Santos: We’re going through difficult times, but this also brings opportunities. For example, there is a growing consensus that we need to change the multilateral system, because what was accomplished and negotiated after World War II is not applicable now. Things have changed, and institutions have to change accordingly and to adapt to new circumstances. I hope we take advantage of this disruption and make the effort to not do away with multilateralism, which would be suicide, but to change the model, to change the system in order to be more effective.

U.N. reform is necessary if we want the U.N. to return to its original mission of preventing wars, mediating in wars that are taking place, and ending wars. There are more than 130 conflicts in the world today — not only in Ukraine and Gaza but around the world, and some are even more vicious than the ones we are seeing in newspapers or on television. The U.N. should be much more involved. Why is it not more involved? Because it has lost the capacity to act because of lack of trust in the institution among many countries and many people. We have to rebuild that trust.

Q: In addition to the lack of trust, another major challenge is the lack of financing. We’re facing trillions of dollars in shortfalls to achieve the U.N.'s 17 Sustainable Development Goals for 2030 and the 2015 Paris Agreement's climate obligations. You’ve called for a 'paradigm shift' in development financing and a much bigger international response, but what we’re seeing are massive cuts to foreign aid in the U.S., as well as cuts in many European countries. How do you see a paradigm shift in financing happening with fewer resources available?

Santos: With the U.S. withdrawing from the Paris Agreement, the reaction should be for countries interested in stopping and correcting climate change to double down. I worry climate change has lost importance on the world agenda when we are suffering its effects more and more. That’s one existential problem we have to address more forcefully and with more determination. The financial aspect is certainly crucial. There, we need new approaches to, for example, leverage the capacity of multilateral financial institutions, involve more of the private sector, and be creative in trying to get sufficient resources to address the problem.

But it’s not only climate change. We have the existential problem of the risk of nuclear war. There, you don’t have to have a huge amount of money. It’s more about political persuasion and the will to address the problem in an intelligent way. The countries that are involved with the nuclear negotiations or that should be involved have to have the will to sit down and talk and get some kind of agreement, because the risk is increasing.

Q: You took on your current role as chair of The Elders in November, only a few days after Trump won the U.S. presidential election. You had experience working with the previous Trump administration when you were president of Colombia, and you said in November that The Elders would work with the new Trump administration to uphold your core values. Now that we’re a little over two months into the new Trump term, do you see any entry points for engaging to uphold the principles that The Elders are advocating for?

Santos: First of all, nobody should renounce their core values. For example, The Elders will continue to try to prevent or stop wars. We will continue to fight for justice and human rights. How? Sometimes through public advocacy, sometimes by private diplomacy. And from our experience, private diplomacy often works better than public advocacy.

For example, the incident between President Trump and the president of my country, Gustavo Petro, at the beginning of Trump’s term was an example of how not to handle things — by insulting each other by tweets. How was that solved? The way they should have solved it from the beginning — by private diplomacy. This is the way to go about trying to continue defending your principles.

Another example is cooperation in order to control the next pandemic. We all know it’s not a question of if it’s going to come, but when and with what force. How can we prepare for that? It is in the interest of everybody, including the U.S., to participate in that discussion. How can you convince the U.S. to do it? Private diplomacy and good arguments. In the long run, people are more sensible than not, so I still hope that this can be done.

Q: I wanted to turn to some lessons we might be able to take from your experience negotiating the 2016 peace agreement in Colombia. One of the lessons you’ve raised from your experience was the importance of listening to victims. Based on your experience in Colombia, could you talk about why listening to victims is so important and why that’s going to be important also in peace efforts in places like Ukraine, Palestine, Sudan, and elsewhere?

Santos: The Colombian peace process was the first and only peace process negotiated under the umbrella of the 2002 Rome Statute, and that had one important element: transitional justice. This is a way to address the concerns of the victims and at the same time be able to have peace. Every peace process, in a way, comes down to where you draw the line between peace and justice. How much justice is a society willing to sacrifice in order to have peace? In that discussion, the victims become important. You cannot satisfy all the victims always, but hearing them, allowing them to participate in the discussion, will legitimize the process. That’s what happened in the Colombian peace process. The victims participated, and we defended the rights of the victims to justice, to reparations, to the truth, and to non-repetition — those four rights were the core of the negotiations. That gave the process tremendous legitimacy.

It’s also a matter of human rights. The victims are the ones that suffer in wars, so they should be heard and taken into account in any process that brings peace. It’s sort of a logical connection. In the case of Colombia, talking to the victims was also re-energizing for me — it gave me the stimulus to continue. Many times, peace processes are difficult, unpopular. But many of the victims, after they told me the tremendous trauma that they suffered, urged me to continue, to persevere. I asked them, 'Why are you so generous? If I explain to you that transitional justice will mean that the perpetrators will have some kind of legal benefits, why are you so generous when you just told me that your daughter had been raped and then killed?' And most of them said, 'Because we don’t want others to suffer what we suffered.' That, for me, was a lesson in life. It showed me how important it is to take into account the victims in any peace process.

Q: Another notable aspect of the 2016 peace agreement in Colombia was the inclusion of women in the peace process and the integration of gender throughout the peace agreement. I think it’s especially important to reflect on that now because we’re celebrating the 25th anniversary of U.N. Security Council Resolution 1325 on women, peace, and security. As we think to the future of the women, peace, and security agenda, what are some of the lessons we can take away from the Colombia peace agreement?

Santos: First of all, my experience is that women are better peacemakers than men. That’s why I’ve been saying for some time that the next secretary-general should be a woman.

Second, women in wars are the most victimized of the victims. That’s why in the Colombian peace process we said we need to have women at the top of our objectives when we’re dealing with reparations for the victims — we need to give them a sort of affirmative action. When you then see women leading the processes of reconciliation, you see how that was an intelligent decision. The lesson here is to give women more space and more power in peacemaking and peacebuilding processes around the world.

This interview published by International Peace Institute Global Observatory on its website on April 16 is reprinted here with permission and minor edits.