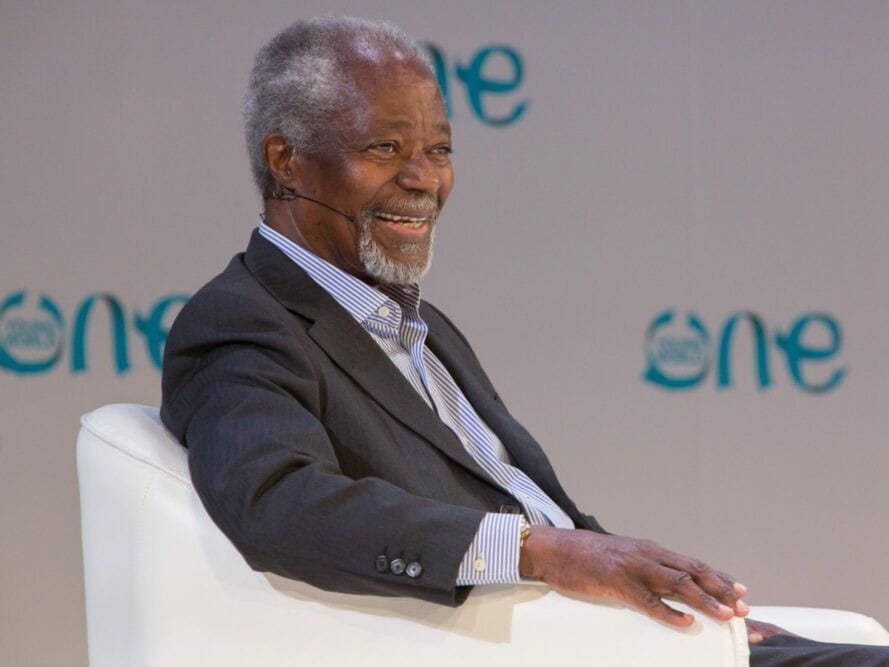

BERN, Switzerland (AN) — Kofi Annan, a Nobel Peace Prize-winning diplomat and charismatic global statesman who rose to become the first Black African secretary-general of the United Nations, embodying many of its biggest successes, failures and challenges, has died. He was 80.

Born in Ghana, Annan served as the U.N.'s seventh secretary-general from January 1997 to December 2006. Afterwards he made his home in Geneva, where he set up his eponymous foundation.