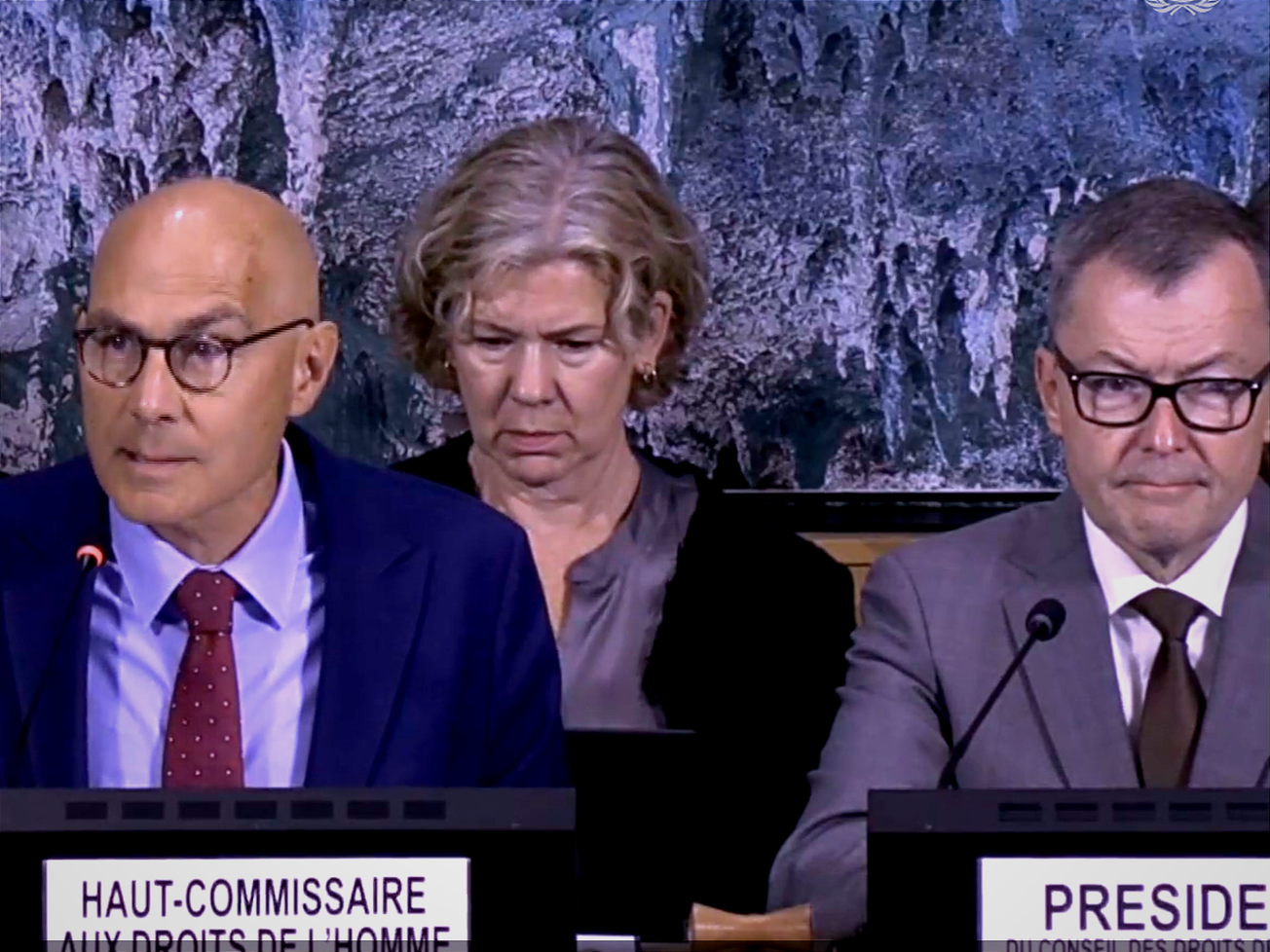

GENEVA (AN) — The U.N. Human Rights Council put China's record under a microscope, pressuring the powerful Asian nation to respect ethnic minorities and allow citizens more basic freedoms.

The 47-nation council's routine examination of China, part of its Universal Periodic Review, or UPR process, focused on China's detention and reeducation camps for at least 1 million Uyghur Muslims and its longstanding crackdown on another ethnic minority, Tibetans.