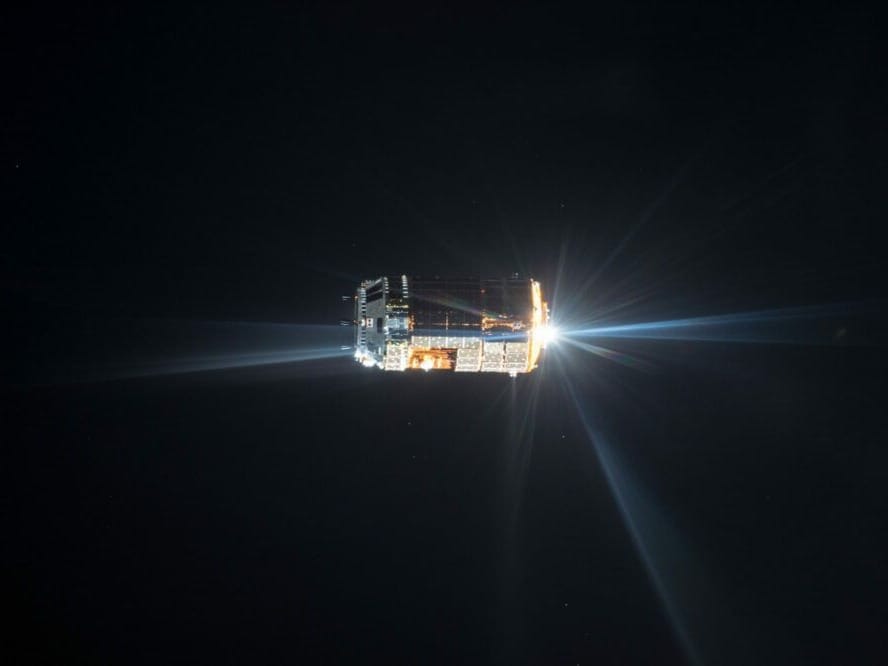

VIENNA (AN) — Ever since the Soviet Union launched the world's first artificial satellite Sputnik I in 1957, United Nations officials and diplomats have adopted a more celestial approach towards their original Earth-bound mission of trying to prevent more wars.

Sputnik triggered the infamous space race between the Russians and Americans, catapulting the space industry and technological advances in both nations. The space race ended in a handshake in 1975 between U.S. astronaut Tom Stafford and Russian cosmonaut Aleksey Leonov during a joint docking mission of the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, the first time two nations collaborated with separate spacecraft.