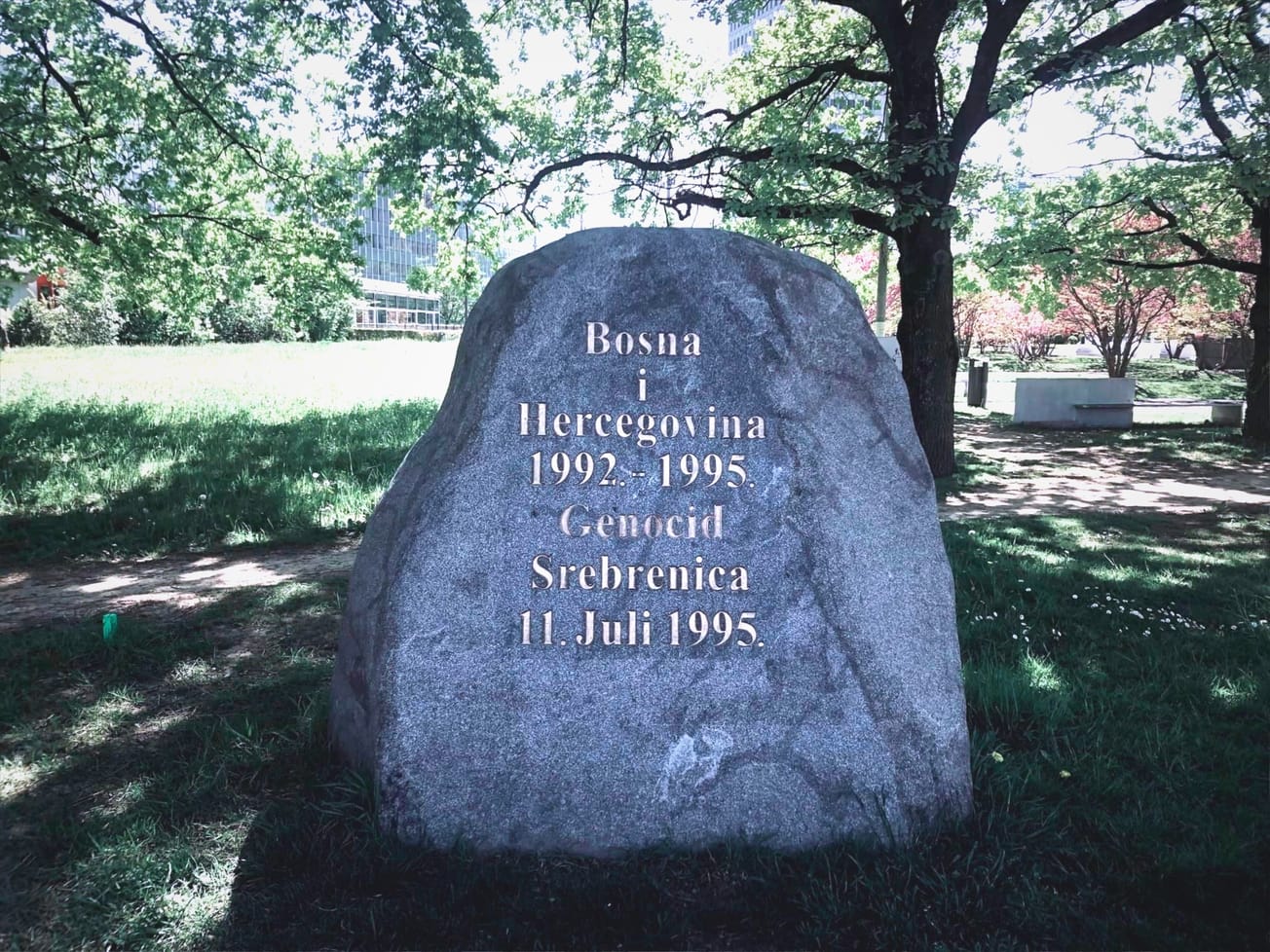

The United Nations General Assembly voted to create an international day of commemoration for the 1995 genocide of more than 8,000 Bosnian Muslims by Bosnian Serbs.

The 193-nation assembly on Thursday approved the resolution on a 84-19 vote with 68 nations abstaining, exposing deep divisions over continuing tensions in Bosnia and Herzegovina.