A century ago, a treaty signing on the outskirts of Paris helped end World War I but raised questions about the reliability of American leadership. Experts at a U.S.-led conference in Paris marking the centennial said many of those same questions remain today.

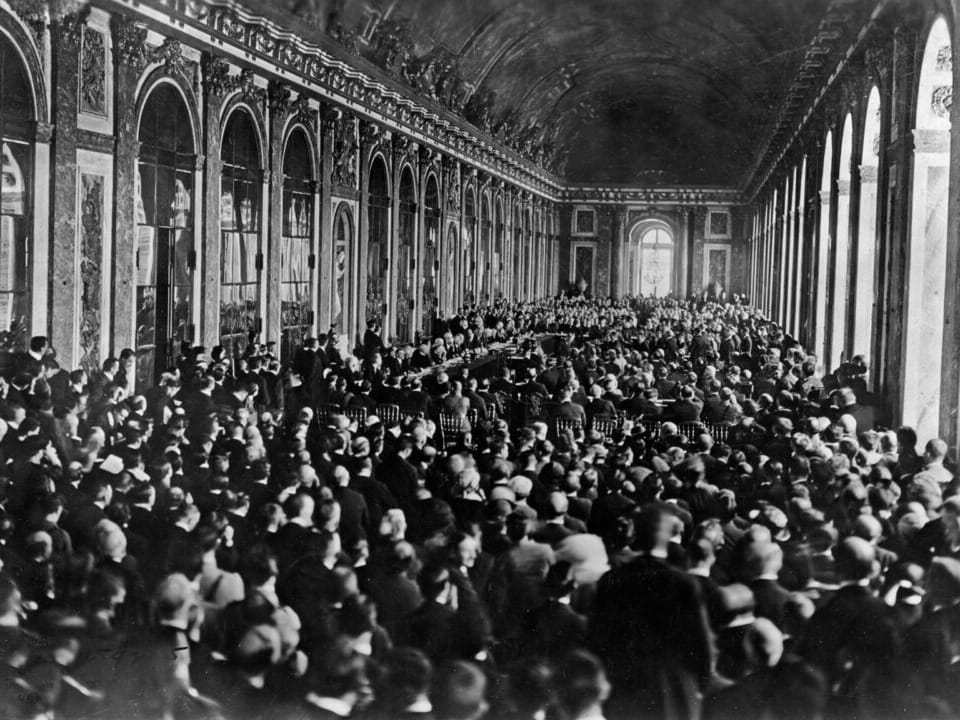

The first of a pair of academic-sponsored centennial conferences kicked off on Friday exploring the significance of the Paris Peace Conference at the Palace of Versailles in 1919. Leaders, diplomats, academics and policy-makers insisted there were some troubling, modern parallels.