GENEVA (AN) — The U.N. health agency issued its first guidance for curbing antibiotic pollution, a leading cause of antimicrobial resistance.

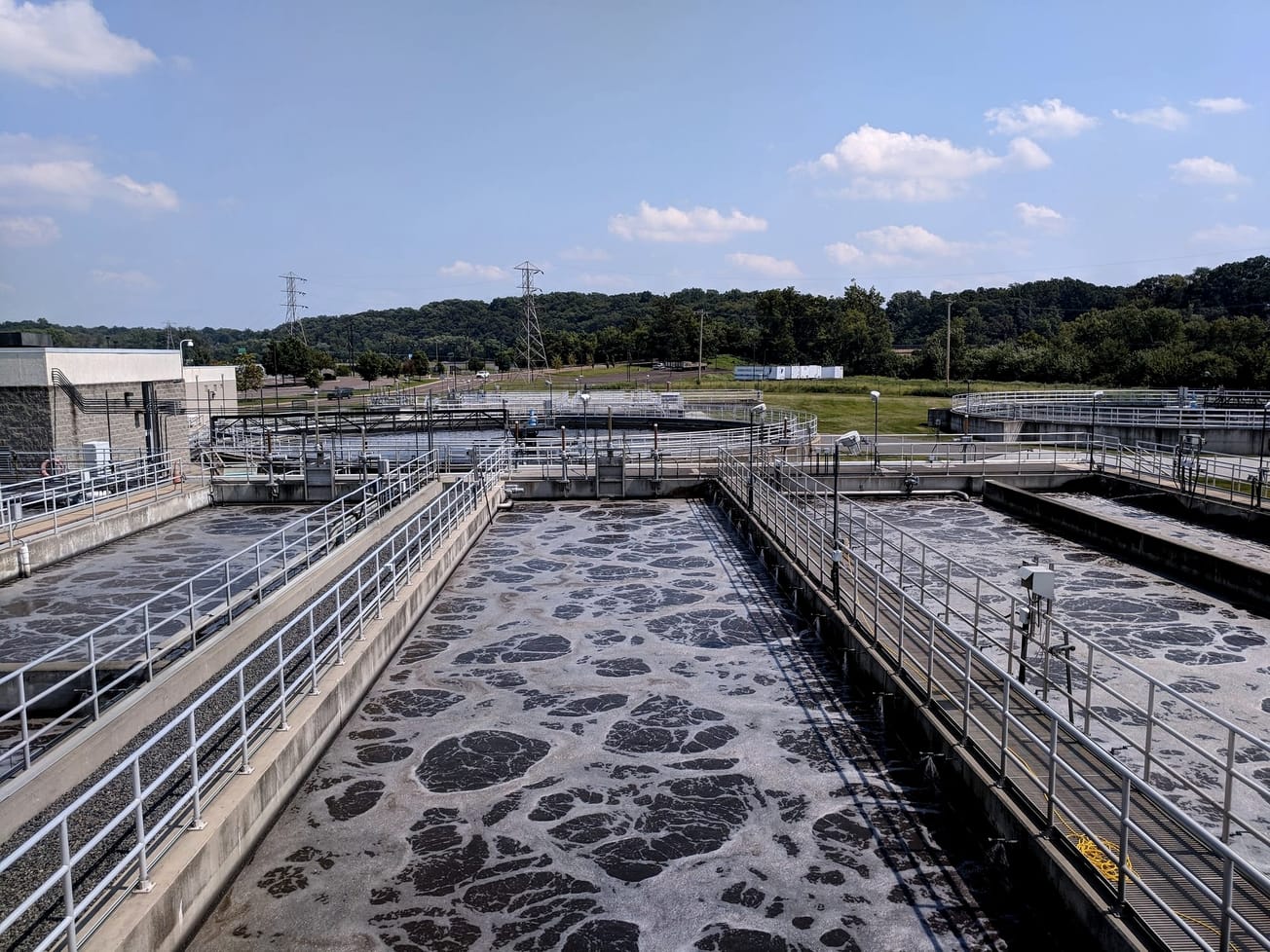

What's new: The World Health Organization's new guidance on Tuesday about wastewater and solid waste management for the manufacturing of antibiotics is intended to prevent the emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance, or AMR. It offers human health-based targets to reduce and address the risks and covers the manufacturing of active pharmaceutical ingredients and their formulation into finished products.